History Statement

Prepared for the Preliminary Questionnaire submitted as part of the King application process for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

Background on

the History of

the King House

and its Historical

Significance

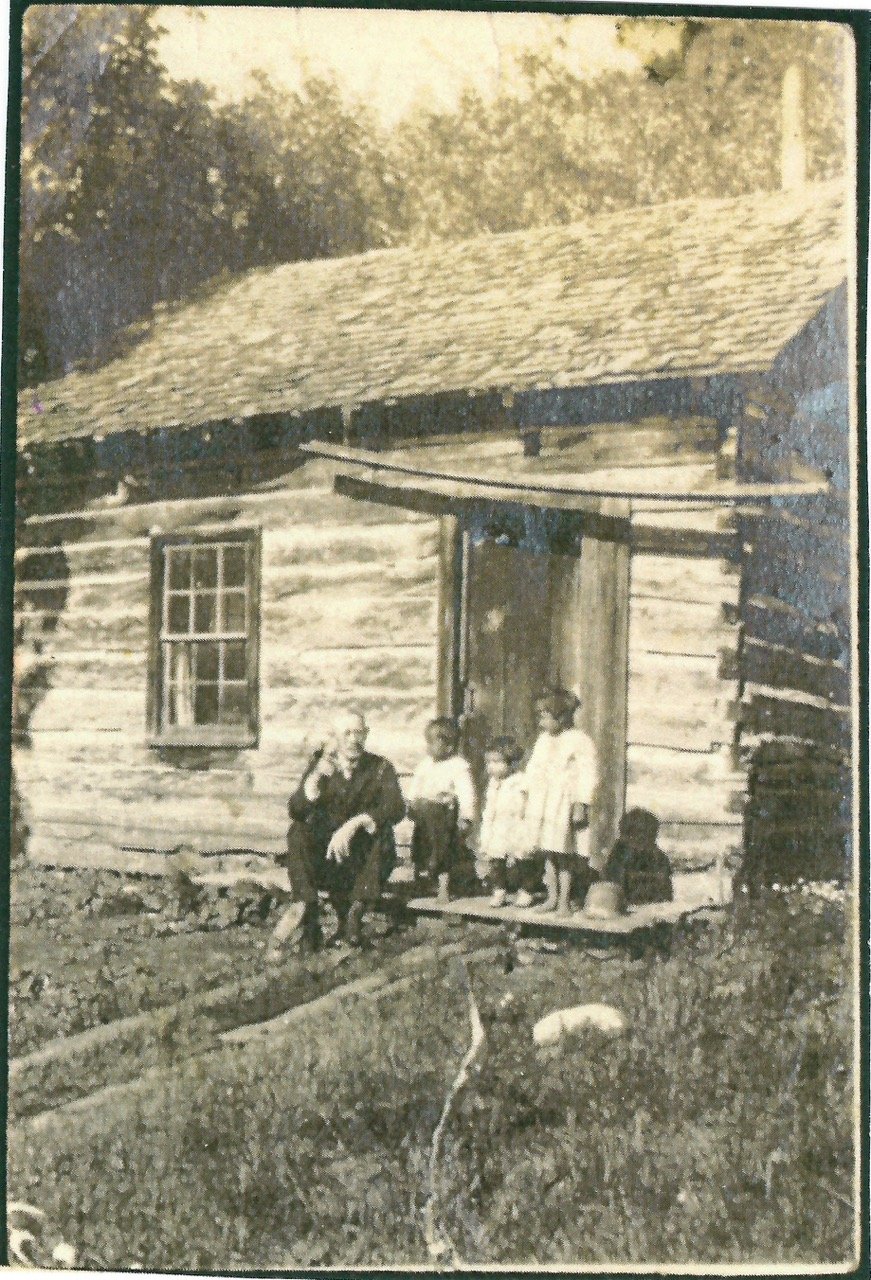

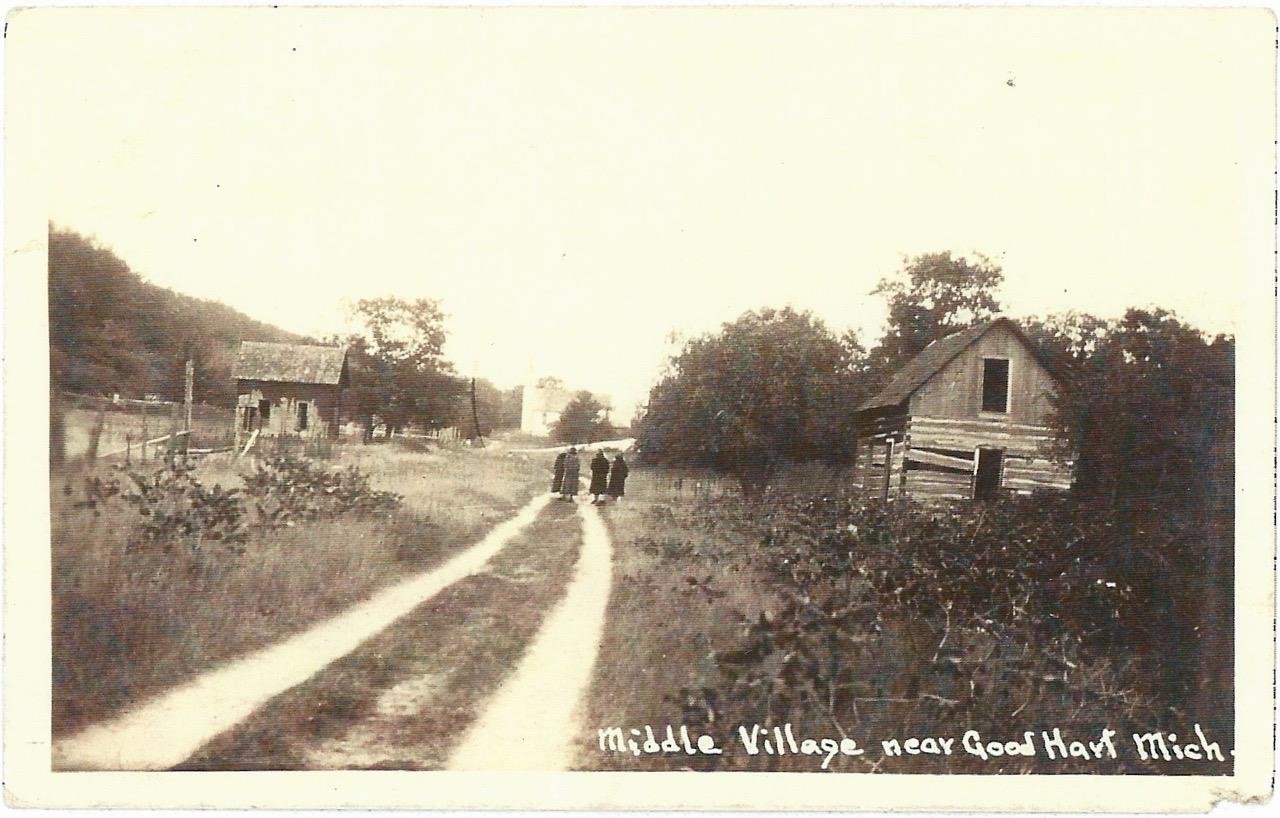

The King House is a 22’x15’ hand-hewn yellow birch log house constructed in the mid-1800’s by Odawa and Indian Agency carpenters on Lot 8 of the then newly platted village of Wa-gau-muck-a-see (“new Middle Village”).¹ Built for and owned by a prominent Odawa family for almost 150 years, the King House is the only example of the 52 log houses that once comprised the thriving Odawa settlement at Wa-gau-muck-a-see that remains relatively unchanged.²

The King House is historically significant because it is unique and because it is located in Wa-gau-muck-a-see (also Wauganawkezee), an important settlement in the history of the Odawa in northern Michigan. As noted in The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, “Middle Village as a whole is significant for the information it can and has yielded on the adaptation of Native American Societies to Euro-American culture as well as their mid-nineteenth century material culture and ecological adaptations.”³

Given the special role of both the house and the village in the history of L’Arbre Croche, the King House provides an authentic site for telling the dynamic story of Middle Village/Good Hart from prehistoric times to the present. The historical significance of Middle Village has already been recognized by the inclusion of St. Ignatius Church and Cemetery which anchors its southern border on the Michigan Historical Register in 1976 and the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.⁴ As a step toward historical recognition in its own right, the King House was recently designated as a Michigan Archaeological Site.⁵

The story of the King House is the story of how the Odawa came to the northern shores of Lake Michigan from Canada in the late-17th century, settling in small seasonal encampments along the shoreline from modern day Cross Village to Harbor Springs in area known as L’Arbre Croche (“the Crooked Tree” and dominating the fur trade, fishing, and farming in the area for 200 years. Wa-gau-muck-a-see (“The Middle Place”), located half-way between present day Cross Village and Harbor Springs, grew to be one of the largest and most influential of these settlements during the 18th century. By the 19th century, the Odawa adapted to the encroachment of white settlers while protecting their cultural heritage through education, religion, and the establishment of permanent settlements such as Middle Village and Good Hart and permanent homes such as the King House. The 20th century brought more change as Middle Village/Good Hart added resorts, cabins, cottages, and eventually year-round homes and resorters replaced both the homesteaders and the Odawa. Middle Village declined and was eventually abandoned as the Odawa, although absorbed into the surrounding towns and villages, kept their identity intact when the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians was reaffirmed by President Clinton in 1994. The King House is historically significant as testimony to this dynamic story of continuity and change over time.

Early Occupation

The Odawa⁶ first came to northern Michigan in the mid-1600’s, pushed west by the Iroquois who were jealous of their extensive trading relationships in food, furs, and local goods among the early French traders and tribes of the region. Moving south from the Straits into what is now Emmet County, the Odawa in turn displaced, some say slaughtered, a small less warlike tribe known as the Mush-quah-tas who lived several miles inland, allegedly for perceived taunts about failed raid against the Huron’s.⁷ Copper artifacts discovered in recent archaeological excavations suggest even older occupancy of the area.⁸ Semi-nomadic, the Odawa generally moved with the seasons, farming and fishing near their semi-permanent lakeside villages in summer, hunting and trapping further south in winter, relocating when the soil became less productive, making long hunting and war expeditions, and trading as they went.⁹

The Golden Age

of the Fur Trade

18th century maritime maps identify Aphitahwaing (“in the middle”) or “Wa-ga-nak-sa” (“the half-way place” in Odawa) as one of the largest of the Odawa settlements in the area known as L’Arbre Croche (“The Land of the Crooked Tree”) that stretched from the Straits to present-day Harbor Springs.¹⁰ L’Arbre Croche was the “grand village of the Odawas” since 1742 and Middle Village was its thriving farming, fishing, and trading center.¹¹ The kinship ties of the Odawa of Wa-ga-nak-sa (also Wauganawkezee) were immense and tangled into all surrounding nations who could be called upon at any time for protection of their Lake Michigan trade routes or as combat allies. They also kept themselves less visible and vulnerable to disease and attack by living in small clan villages. John Wright, ”Michigan’s Indian poet” who lived in Middle Village for many years,¹² wrote that in the late 18th century “So populous was the settlement at this time that an Indian might walk a distance of a full twenty miles along the shore and find a wigwam every few rods.”¹³ The Odawa were the middle men in all trade negotiations at Michilimackinac and were always considered the “most expert on the warpath and wise counselors.” Every nation “far and near” deposited a peace pipe at Michilimackinac and pledged to let the Odawa to settle disputes between them.¹⁴ The long association and ¹accommodation of the Odawa with the French (traders, missionaries, and governors) had led to the creation of a “middle ground” whereby participants sought to settle differences through mediation to avoid the disruption of war and violence.¹⁵

Until the imposition of British rule after French and Indian War in 1760 and the turbulence of the American Revolution (1776-1783), the 18th century was a golden age of great power and prosperity for the Odawa of Middle Village and L’Arbre Croche.¹⁶ In 1820 Jedidiah Morse, minister, “father of American geography” and father of Samuel Morse took an interest in the “civilizing” and Christianization of Native Americans bordering American settlements. For two winters and with the approval of the Secretary of War, he went to see conditions for himself. He found that the Odawa at Michilimackinac were a very different nation than what he’d been led to believe. He noted their principal base was Wauganawkezee, one of at least five major villages dotting the shoreline and the one that impressed him the most. The Odawa had long cultivated corn, potatoes and pumpkins selling their surpluses to the Mackinac market. Morse estimated that there were 4,700 Odawa in as many as 52 villages plus 1,200 merchants and traders, military personnel and metis families in L’Abre Croche and credited the “civilizing” influence of the Catholic Church on its development.¹⁷

Missionary influence

Jesuit missionaries visited, some say as early as 1691, and played a significant role in encouraging permanent settlement. Father Pierre du Januay, the Jesuit priest who ministered to the Odawa throughout L’Arbre Croche from 1727-1766, established the first Catholic mission in a longhouse built by the inhabitants at (old) Middle Village a mile south of the current (new) Middle Village in 1741. He also provided important contacts for the Odawa with French colonial offices in Montreal and Quebec. After Fr. Du Januay was forced to leave the area around 1766 by the British, the ogemuk (leaders) of L’Arbre Croche repeatedly petitioned first the British and then after the entire area was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the American government for a new priest. Fr. Gabriel Richard was finally sent from Detroit in 1799, most likely meeting with the Odawa at (old) Middle Village where the center of population had moved after the mission at Cross Village was abandoned. Other missionary priests followed, notably Fr. (eventually Bishop) Frederic Baraga in 1831 who founded or re-founded nine missions in the area and dedicated the first permanent birch-bark church building at (old) Middle Village to St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1833. Fr. Baraga was impressed that the Catholic Odawa at Middle Village would gather on Sundays to sing and pray whether or not a priest was present. The Protestants also had a presence in the area. Presbyterian missionaries established a church and school at the Odawa settlement of Good Hart a mile north of Middle Village in the 1850’s and several Middle Village children attended the Protestant school on Beaver Island as early as 1827.¹⁸

Throughout this period of great political and social change, the Odawa of Middle Village had continued to live much as their ancestors had, fishing and farming in their lakeshore villages in the summer and hunting and trapping further south in the winter. Gradually however they began to take advantage of the schools, training, and material goods offered by the churches and the agents of the US Office of Indian Affairs. Prominent ogemuk and their families attended schools established by the Jesuits and Protestants alike, cleared more farm land, and began to build permanent log homes in their villages.¹⁹

Platting Middle Village

Just as the Odawa began to transition into a more permanent settlement patterns in the early 1800’s, the Michigan Territory was moving toward statehood and the press of white settlement created a demand for more and more land. Early in 1835, the Indian Agent at Mackinac Henry B. Schoolcraft was asked to “ascertain whether Indians north of the Grand River would sell their lands and if so on what terms.”²⁰ The ogemuk of many Odawa bands gathered in Little Traverse (Harbor Springs) that May and selected Augustin Hamelin, Jr. (Kanapima) of L’Abre Croche , educated first at the Catholic school in Harbor Springs and then at seminaries in Cincinnati and Rome, as their “head chief” with authority to negotiate for all of the Odawa bands in Washington. The result was the Treaty of Washington (1835) in which the Odawa sold most of northern Michigan, some 13.7 million acres, for money, goods, benefits, and services that amounted to about $6 an acre.²¹ Unaccustomed to a cash economy, many Odawa quickly spent or were defrauded of their allotments. Odawa leaders soon petitioned for redress, leading to a new round of negotiations and the Treaty of Detroit (1856) which was intended to settle outstanding land and compensation issues.²² From the perspective of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBB), neither the U.S. Government nor the State of Michigan has ever met its obligations under either Treaty. As a result, the LTBB recently brought a federal lawsuit against the State of Michigan, reasserting their rights over treaty-established reservation lands, including Middle Village/Good Hart, and making the King House and what it represents as currently relevant as it is historically significant.²³

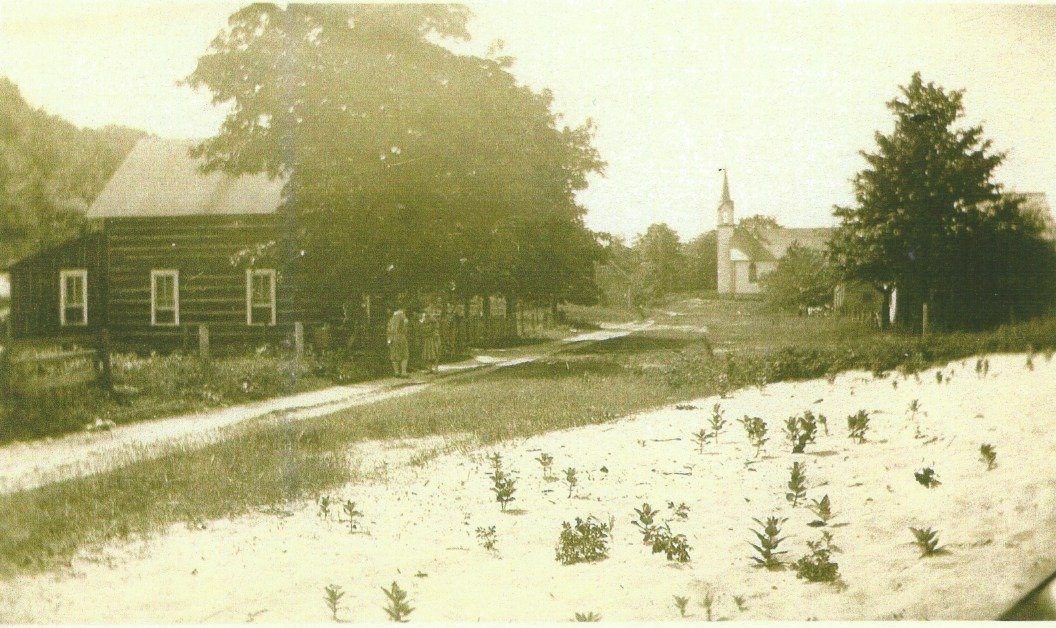

By the time of the treaties in 1835-56, Middle Village had become a more permanent settlement. The “Catholic” Odawa of L’Arbre Croche already had the reputation of being “more civilized”, e.g. living in permanent settlements rather than moving with the seasons, farming and fishing rather than trapping and hunting, and going to church and to school. The 1833 church dedicated by Fr. Baraga burned and a new one, built about a mile north in “new” Middle Village, prospered. That building also burned, probably in 1861, and was quickly replaced. Local Odawa built permanent homes of hewn logs on Odawa-owned land around the church, a school was added in 1857, and Catholic priests visited regularly. The community expanded when Presbyterians established their own mission and school in a settlement known as Good Hart (for its ogemuk who was known as “he who is good-hearted”) about a mile north in the mid 1850’s.²⁴

The evolving permanency of Middle Village is relevant to the story of the King House because Father Francis Pierz who succeeded Fr. Baraga and several of the ogemuk of Middle Village, among them one of the first owners and likely builder of the King House, had purchased land designated as “reserved” for Indian occupancy in the 1835 Treaty near old Middle Village in 1844. Fr. Pierz and Augustin Hamelin, Jr. encouraged local Odawa residents to purchase their land rather than accept is solely as a treaty allotment in order to assure land titles.²⁵ In 1846, they also purchased government lot 4 in section 36, township 37 North, Range 7 west (33.28 acres) which was parceled off into 39 lots and the plat map showing their size and location was recorded as the village of Wa-gam-muck-a-see (“Middle Way”) in 1850. By 1855, the Middle Village Odawa had purchased 1,467.28 acres near their old and new settlements.26 An 1849-54 map of L’Arbre Croche shows²⁶ structures at the exact site of Middle Village and about the same number scattered along the shore to the north for about 2.5 miles.²⁷

Architecturally, these Middle Village houses followed the squared hand-hewn log “pen” (also known as “crib”) design (one room, sometimes with an upstairs sleeping loft) brought by white settlers moving west in the 18th and 19th centuries. Architectural historians believe that horizontal log building construction originated in northern and eastern Europe and was introduced to colonial American by Finnish and Swedish settlers along the Delaware in the early 17th century. The economy, adaptability, and expandability of the form explains its rapid adoption throughout colonial America and then with western expansion well into the late 19th-century.²⁸

The King House is a prime example of the type. Built of then readily available yellow birch logs, hewn square by hand and assembled by stacking logs connected at the corners by a simple square notching technique and secured by stone and wood chinking and locally made daubing, the King House measures 22’x15’ with a door on the south wall, one window on the west, and two on the north. Typical of the architectural style, the House has a second story loft reached by steep, narrow steps. According to circa 1900 pictures, the House also had a kitchen annex on the east side, accessible through a door in the east wall of the main structure. Historic photographs point out some of the historic architectural features of the House, including the stoop, first floor ceiling, and suggestion of a chimney for a stove. Clearly the House, as those who lived in it, changed with the times.

Ownership of Lot 8 and the King House29

The 1850 plat map of the Village of Wa-gau-muck-a-see clearly identifies Lot 8, across the road and about 50 yards north of the lots owned by St. Ignatius Church.³⁰ The first owners of Lot 8 in County records were William and Julia Bwanishing who sold it to Peter Onassano (which translates from the Odawa as “King”) in 1866 for $5. Peter Onasano/King was one of the ogemuck (principal men) of Middle Village. He had been involved in selecting the Odawa representatives who went to Washington to negotiate the Treaty of Washington in 1835, signed the 1842 petition asking the U.S. Government to allow Indians to purchase land that eventually led to the Treaty of 1856, and worked with Fr. Pierz on the 1844-1846 purchase of old and new Middle Village lots.³¹

The story of the ownership of Lot 8 on which the King House was built is qualified by uncertainty about the family relationships and spellings of names in tax and title records. Odawa names were spelled differently by different writers who heard different pronunciations, complicating efforts to track individuals and families. Title researchers also report that Odawa titles were frequently held in women’s names for protection against the efforts of whites to defraud their Indian owners. Since oral histories line up closely with the official record, however, there is greater confidence about Lot 8 than many of the other parcels in Middle Village.³²

In their helpful study The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County Michigan, published by The Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in 1995, Wes and Eleanor Andrews surmise that a house was built on Lot 8 sometime after 1867. Other evidence, however suggests that the house may have been there much earlier since maps show that log houses were being constructed by Odawa and Indian Agency carpenters as early as 1844. A topographical map prepared 1849-1854 by the U.S. Army shows “approximately 26 structures at the exact location of present day Middle Village”. 1874 tax records list Peter Onaasano as the owner of Lot 8 and indicate that a structure was there in 1872- 1876 and again in 1888-1908. Wes and Eleanor Andrews suggest that the house may have been built by Joseph King (1847-1918), son of Odagamiki King (another spelling of Peter Onaasano? Or his wife’s name?).³³

In 1883, the surviving heirs of Peter Onaasano sold Lot 8 to his widow Ellen Nebamoqua who in turn sold it to Rosine/Roosen Otaw-gaw-me-kee in 1890 in a transaction witnessed by Joseph King Odagamekee (Peter’s son? Rosine’s husband?). In a by then familiar pattern, Rosine Otagomkee/King lost title to Lot 8 for failure to pay taxes in 1893 but, less commonly, bought it back from the State in 1898. From then on the title and family line is much clearer.

Lot 8 and the King House was reported by family and neighbors to have been the residence of Joseph King who lived there until he died in 1918. The House was then passed to his oldest son Tom King (1871-1939) who, with his wife Eliza, both appear on the 1909 Durant Roll. After Eliza’s death, Tom King lived in the house, often joined by his daughter Isabelle (King) Ramage and her daughter Mathilda (nee Ramage) Allison until his death in 1939.³⁴

From 1941-1969, the owner and taxpayer of Lot 8 was listed as Alec J. King (1902-1969), Tom King’s eldest son, although it is likely he did not live there. After Alec King’s death, no one paid taxes on the House until a neighbor Martin B. Breighner, bought the property for back taxes in 1977. At that point, Mathilda (King) Ramage Allison, Tom King’s granddaughter and Alec J. King’s niece, who had lived at the house as a child, learned of the sale and after clearing the title with her cousins who were sons of Tom King’s brothers, repurchased Lot 8 in 1979. In the tradition of the women in her family, Mathilda Allison, who had moved to California, had become a well know quill artist and was committed to keeping the traditional crafts she had learned from her elders in Middle Village alive.³⁵

By the time Mrs. Allison reclaimed Lot 8, the House was in significant disrepair. A tree was growing through the main room, the roof had collapsed, and kitchen annex had rotted away. She then hired Bill Glass, a local contractor, for some $8,000 to “save the house” as he recalled her saying.³⁶ Mr. Glass took the House apart log by log, built a new foundation (the original was simply a large rock on each corner) in the exact location, and reconstructed the exterior walls in the same order, replacing rotten birch timbers with pine. He also rebuilt the second story, replaced caved-in roof, and installed repaired windows and doors in the original locations. While the reconstruction was not always historically accurate, it served the purpose of preserving the House in very close to original form and can be corrected by knowledgeable contractors who specialize in historic restoration.³⁷

Mrs. Allison was listed as the owner and taxpayer of Lot 8 until she died in 1990. Her husband continued to pay the taxes and claimed title from his wife’s estate in 2004 in an Affidavit of Title that reviews the ownership of the property from 1898 forward. In 2006, Mr. Allison sold the property to his son who sold it to the King House Association, which had been organized for that purpose, in 2015. The family’s hope was that the House and the memory of those who had lived there would be preserved. The application for recognition of the King House on the National Register of Historic Places is submitted in their honor.

The next chapters

The historical significance of the King House rests not only on the importance of Middle Village in the history of the Odawa and the prominence of the King family who owned and cared for it, but also on its witness to the dramatic social and economic changes in Middle Village over the 150 plus years since it was built. The fortune and fate of the King House and Middle Village is a case study in the impact of social and economic change on ethnic and cultural fortunes and identity.

Within a generation of the construction of the King House, homesteader streamed into Northern Michigan, displacing and disrupting the Odawa community while transforming the social and economic life of the area. Villages grew into towns, fishing and farming were overtaken by logging and then by tourism and new traditions grew up on top of the old. The transition to a resort economy was well under way by the turn of the century. In Good Hart for example, the government school established in 1860, became the Lamkin store after the school closed and then the Lamkin Lodge when a hotel annex was added in the early 1900’s.³⁸ The Odawa in Middle Village acclimated to these changes by becoming hired labor in the farms and timber mills and in the 1930’s by reviving traditional Odawa crafts, especially bead and quill work, to sell in the stores, one just up on the bluff in Good Hart, which grew up to cater to the summer visitors.³⁹ As already noted, Mathilda King Ramage Allison who saved the King House became a nationally recognized quill artist in keeping with her family’s artistic traditions.⁴⁰

A 1939 Michigan survey of Indian groups in the state reported 22 Odawa families in the Middle Village/Good Hart area, half of whom lived in Middle Village.⁴¹ Keith Lamkin, whose family connections to Good Hart/Middle Village go back 100 years⁴², remembers when he was a boy running through Middle Village in the 1930’s, Tom King would sit on the porch of his small log house and tell stories to the children about the legends of the area. Keith reported that “He was like the mayor of the village” who settled disputes and handled problems brought to him by his Middle Village neighbors.⁴³ In this respect, Tom King much like his ancestor, ogemua Peter Onassano who had purchased Lot 8, most likely built the house, and had served as a leader of Middle Village so long before.

The King House has thus borne witness to the dramatic social and economic changes in the area that have affected Middle Village/Good Hart over time, from its earliest Native American inhabitants, to the Odawa, the homesteaders, the resorters, the summer cottagers, to the growing group of year-round retiree residents of today . The goal of the King House Association is to use a fully restored King House as an historic site for telling the stories of all of those who have lived in Middle Village/Good Hart and how their lives have crossed and woven together to create the rich social and cultural fabric that has shaped this special place.

Bibliography

(n.d.).

Andrews, Wes, and Eleanor Andrews. An Archaeological Survey of of the St. Ignatius Church Cemetery in Emmet County, MI. Petoskey, MI: Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, 1993.

—. The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan. Petoskey, MI: The Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, 1995.

Blackbird, Andrew J. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan. Ypsilanti, MI: Ypsilanti Job Printing House, 1887.

Bomberger, Bruce D. #26 Preservation Briefs: The Preservation and Repair of Historic Log Buildings. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1991.

Cardinal, Jane, and Connie Cobb. The Place Where the Crooked Tree Stood, a History of L’Arbre Croche Focusing on the Settlements of Good Hart and Middle Village. Good Hart, Michigan: The Crooked Tree Book Company, 2012.

Clifton, James A, George L Cornell, and James M McClurken. People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwa of Michigan. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Indian Press, Grand Rapids Inter Tribal Council, 1988.

Deeds, Emmet County Register of. “Warranty Deed.” Vol. Liber C. Petoskey, Mi, July 10, 1866. 172.

Eckerle, Beth Anne. “Fit for a King: Restoration and Preservations effort saves last remaining Odawa home in Good Hart.” Imagine: Living in Emmet County Michigan, 2016: 45-47.

Glass, Bill, interview by Jim Clarke. (2015).

Hannah, Susan B. “Ownership of Lot 8 Timeline.” Good Hart, Michigan, 2016.

Hemenway, Eric. “The Road to Home: the Odawa Fight to Stay in Wagnakising, Land of the Crooked Tree”. Petoskey. October 24, 2016.

—. “Waganakising: Land of the Crooked Tree.” Essence of Emmet: A Four-Part Historical Series About Emmet County, Michigan, 2014: 6.

Herek, Ray. “Wa-ga-nak-sa or Middle Village Has Been Around.” Harbor Light, September 2-8, 1971: 13-20.

Kramanski, Theodore. Blackbird’s Song: Andrew J. Blackbird and the Odawa People. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 2012.

List of Historic Sites in Emmet County, Michigan. Jan 7, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Michigan_State_Historic_Sites_in_Emmet_County.

Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. “A Tribal History of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBB).” Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. January 7, 2016. http://www.ltbbodawa-nsn.gov/TribalHistory.html.

Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians b. Rick Snyder, Governor of the State of Michigan. Court File No. 15-850 (Western Distric of Michigan -Southern Division, August 21, 2015).

Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. Our Land and Culture: A 200 Year History of Our Land Use. Petoskey, MI: Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, 2005.

McClurken, James M. Gah-Baeh-Jhagwah-Buk: A Visual Cultural History of the Little Traverse Bay Banks of Odawa. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Museum, 1991.

—. Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 2009.

McDonnell, Michael A. Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2015.

Michigan State Archaeologist. “State Site No. 20EM156.” Lansing, MI: Michigan State Housing Development Authority, 2016.

Sullivan, Kathy. “Quill Work on Display.” The Pioneer, February 19, 1991: 3-4.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2011 (20th Anniversary Edition).

—. The Middle Ground: Indians, empires, and republics in the Great Lakes region, 1650-1815. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991 (new edition 2011).

Wright, John C. The Crooked Tree: Indian Legends of Northern Michigan and a short History of the Little Traverse Bay Region. Harbor Springs, MI: C. Fayette Erwin, 1917.

1 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 72)

2 (Andrews & Andrews, 1995, pp. 145-147) (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 36) (Eckerle 2016)

3 (Andrews and Andrews 1993, 201)

4 (List of Historic Sites in Emmet County, Michigan 2017)

5 (Michigan State Archaeologist 2016)

6 “Odawa” is the preferred local spelling and pronunciation of the Anglicized Old French name “Ottawa,” which in Algonquian means “traders”. (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians 2016)

7 (Wright 1917, 29-33) (Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan 1887)

8 (Andrews and Andrews, An Archaeological Survey of of the St. Ignatius Church Cemetery in Emmet County, MI 1993)

9 (McClurken, Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians 2009)

10 These maps label all of western Michigan from the straits south as “Ottawa lands.” (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 6). Middle Village is also clearly identified in a 1825 reproduction of a map Territoire de Michigan, available in the Local Archive room of the Petoskey Public Library

11 (Kramanski 2012, 5)

12 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 435-439)

13 (Wright 1917, 41)

14 (Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan 1887)

15 (White, The Middle Ground: Indians, empires, and republics in the Great Lakes region, 1650-1815. 1991 (new edition 2011), 33)

16 (Andrews and Andrews, An Archaeological Survey of of the St. Ignatius Church Cemetery in Emmet County, MI 1993) (McClurken, Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians 2009)

17 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012). See also (Herek 1971, 15)

18 (Herek 1971)

19 (Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan 1887). An excellent eyewitness account of this period by an Odawa chief, interpreter, public official and author.

20 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 24)

21 (McClurken, Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians 2009)

22 (McClurken, Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians 2009)

23 (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians b. Rick Snyder, Governor of the State of Michigan 2015)

24 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 173)

25 Odawa frequently lost title to their land through failure to pay taxes or register heirs, practices alien to traditional land use practices. By the end of 19th century, 90% of the land allotted through the 1836 and 1855 Treaties was owned by non-Indians (Cardinal and Cobb 2012) (McClurken, Our People, Our Journey: The Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians 2009).

26 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 67, 172-75) (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 36-37)

27 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 172)

28 (Bomberger 1991, 1-4)

29 A timeline of the ownership of Lot 8, with bibliography, is Attachment A (Hannah 2016)

30 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 37) for a copy of the 1850 plat map.

31 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 36-37) see also (Hemenway 2014) and (Hemenway 2016)

32 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 173)

33 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 145-47)

34 (Eckerle 2016) for stories about Tom King’s leadership role in Middle Village.

35 (Sullivan 1991)

36 (Glass 2015)

37 A structural analysis of the King House carried out by preservationists has provided the King House Association Board with recommendations for carrying out a more historically accurate restoration.

38 (Cardinal and Cobb 2012, 243-280)

39 (Andrews and Andrews, The Middle Village Archaeological Survey and Properties of Traditional Value Project, Emmet County, Michigan 1995, 183-186)

40 (Sullivan 1991)